Why Archetypes Must Be Abandoned in the Study of Myth, Folklore, and Legend

For too long, the study of myth, folklore, and legend has been dominated by archetypes—universal symbols supposedly embedded in the human psyche. Influenced by Carl Jung’s “collective unconscious,” this framework reduces complex, culturally specific traditions into repetitive psychological templates. While archetypes may help explain basic fears (e.g., fire, darkness, heights), their application to mythology is flawed and must be reconsidered.

The Flattening of Cultural Memory

Archetypes compress the living, layered memory of a people into metaphors. The hero’s journey, wise elder, or trickster god appear across cultures not as psychological blueprints but as reflections of real social structures, biological functions, or even encounters with anomalous beings. Calling Quetzalcoatl a “trickster” or Osiris a “dying-and-rising god” erases centuries of historical nuance and encoded knowledge.

Archetypes Block Investigation

Labeling a figure an archetype is a conclusion, not a question. It discourages inquiry. Instead of asking why ancient civilizations described feathered serpents or sky beings, we accept them as symbolic. This ignores the possibility that these motifs point to real, cross-cultural encounters or cosmic patterns. Archetypes are intellectual shortcuts that halt discovery.

Myths Are Fractal, Not Archetypal

Unlike static archetypes, myths are fractal—evolving patterns that repeat with variation, adapting to different environments and epochs, like nature’s recursive designs. Fractals allow similarity and specificity, showing how a Mesoamerican serpent deity, Chinese dragon, and Indian naga share cosmic roles while retaining local identities. Myth is not a psychological code; it’s an evolutionary language.

Fractals preserve the core while evolving the form.

The Tyranny of Universality

Archetypes’ allure lies in their claim of universality, but this is their flaw. Not all cultures view the divine, heroic, or monstrous alike. By forcing global traditions into preset molds, archetypes impose a Western psychological lens on diverse cosmologies. This isn’t synthesis—it’s erasure.

What About Instincts?

Fears of fire, darkness, or snakes may be biological instincts, not archetypes. They shape storytelling but don’t define myth. A child’s fear of the dark doesn’t make Hades a Jungian projection; it may reflect early humans’ tangible understanding of caves, death, or the underworld.

Toward a Fractal-Memory Model

We must explore myths as fractal memory—recursive patterns reflecting biology, environment, and culture. Legends are not psychological templates but echoes of real events, encoded technologies, or ancestral experiences, preserved through oral traditions. They are compressed data, memory echoes, and evolution captured in narrative form.

Follow the Evidence

To follow myth is to follow the fractal road—a path through memory, recursion, and revelation. It winds through ancient sightings, biological echoes, and sky-born coordinates, always preserving the essence while evolving the form.

The cover image—vibrant bird-human hybrids from ancient art—illustrates this argument. These are not archetypes but potential memories of evolutionary offshoots, visitors, or lost beings.

The Manticore: A Tiger’s Mythic Echo

The manticore, a mythical beast with a human face and lion’s body, may reflect distorted memories of tigers, their fierce features exaggerated through oral retellings—a fractal process preserving a real animal’s essence. The "spiked tail" could even originate from misunderstood tiger stripes seen under motion or foliage.

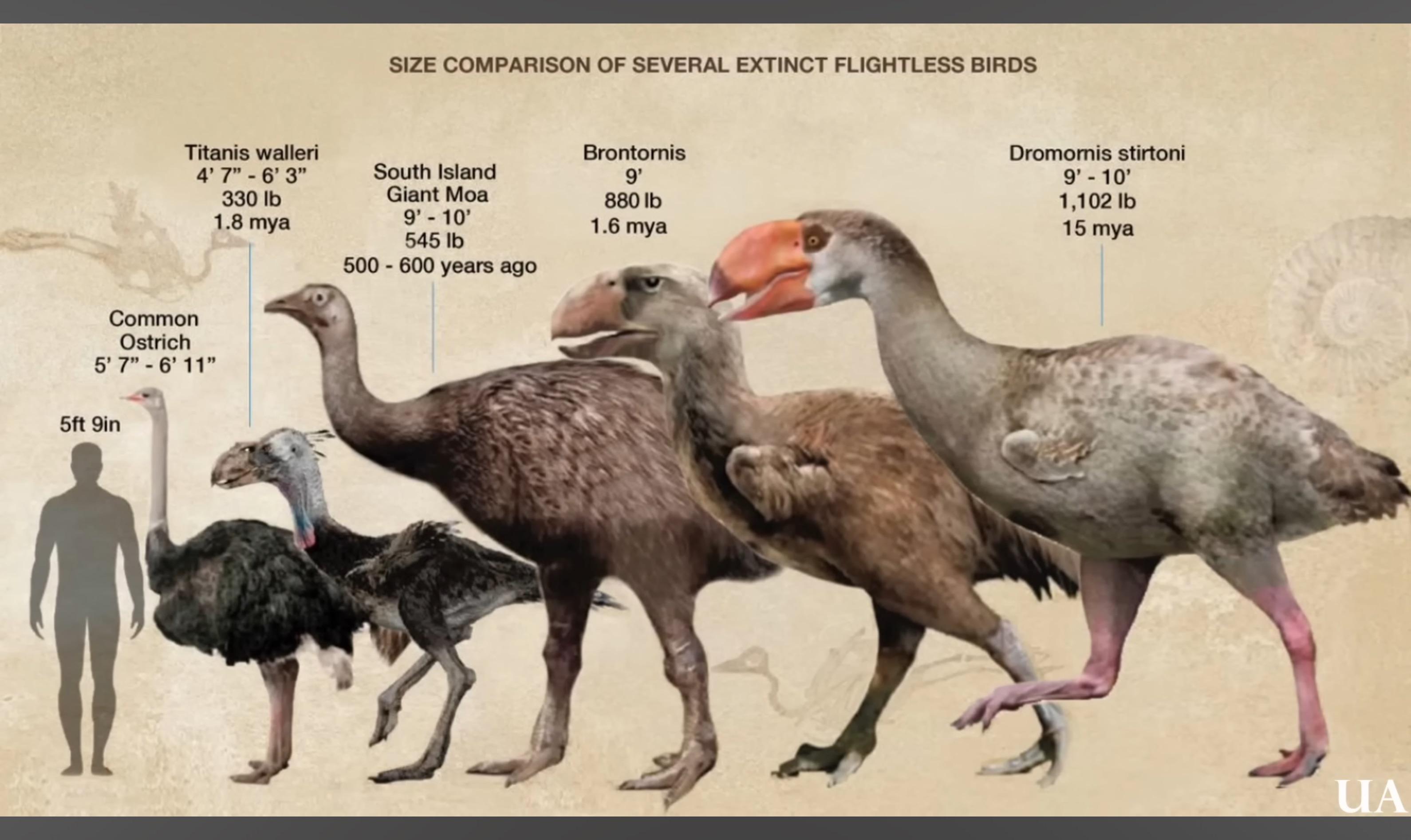

Talking Birds as Sky Deities

Many birds, like parrots and crows, mimic human speech. A large, extinct bird with similar abilities could have inspired myths of talking sky-beings, its human-like sounds evolving fractally into deities like Garuda or the thunderbird. If such a creature mimicked names or speech, ancient humans may have perceived it as divine.

When Myths Name the Stars

When myths name star systems—Orion, Sirius, Pleiades—they are not poetic flourishes or archetypal shorthand. They are precise signals, compressed through millennia, pointing to real experiences, astronomical knowledge, or cosmic encounters.

Archetypes flatten this: Orion becomes a “hunter,” Sirius a “guide,” Pleiades a “sisterhood.” But why did pre-telescope civilizations, from the Dogon to the Mayans, name these exact stars? The Dogon knew Sirius B’s 50-year orbit—though some debate modern influence, the consistency of their astronomical traditions remains striking. Egyptian pyramids aligned with Orion’s Belt. The Pleiades anchored calendars across Greece, Mesoamerica, and Oceania.

This consistency suggests cultural diffusion or a shared origin. In the fractal-memory model, these names are vectors, encoding observations or encounters with beings tied to those stars. Archetypes reduce cosmic precision to projection, but myths don’t point to emotions—they point to the sky.

Conclusion

Archetypes, while simple, must be abandoned as the foundation for mythological study. They obstruct inquiry, erase specificity, and rely on unprovable assumptions. Myths are living records, fractal in nature, pointing to truths waiting to be decoded.

It is time to stop projecting and start listening—by decoding the fractal patterns of myth, we can rediscover truths that connect us to our ancestors and the cosmos.

Leave a comment